When we think about cities and urban life, we often focus on infrastructure, culture, commerce, nightlife, and density. In metropolises where there seems to be an endless array of activities—especially for adults—play rarely enters the conversation. Yet, the act of playing should be considered a vital part of urban life. Play directly influences how we shape our future cities—starting with how children engage with their environments. The experience of play, and more specifically, the design and presence of playgrounds, leaves lasting impressions on how young people grow up in cities. These spaces form a child's first, physical connection to the urban landscape. In this way, play deserves far more attention in conversations around urban wellness, livability, and the design of public space.

A Brief History: Isamu Noguchi's Vision of Urban Play

One of the most notable early explorations into the role of play in the city came from Isamu Noguchi's Play Mountain, designed in 1933. A visionary in both sculpture and landscape, Noguchi sought to redefine how children engage with their environments—not through prefabricated slides or swings, but through landforms and sculptural terrains. He believed in play as a spatial, imaginative, and physical act rooted in exploration.

"I think of playgrounds as a primer of shapes and functions; simple, mysterious, and evocative—thus educational" Isamu Noguchi

Noguchi's work marked a shift in how playgrounds were conceived. Rather than offering predictable features with singular uses, he invited children to interpret the environment on their own terms. His philosophy encouraged creativity, autonomy, and even risk—qualities largely designed out of today's overly standardized and hyper-safe playgrounds. His approach laid the groundwork for rethinking urban play as a meaningful, interactive, and spatially rich experience.

Eventually, Noguchi's visions moved beyond paper architecture and were realized in more than 20 public works across the world. His Play Mountains and Playscapes took physical form in cities internationally, culminating in his final and most ambitious project: Moerenuma Park in Sapporo. Spanning 454 acres and taking over two decades to complete, the park continues to inspire both children and adults to rethink their relationship with the environment. It encourages movement, exploration, and bodily engagement in ways that few contemporary everyday urban structures—shopping malls, train stations, or infrastructural facilities—can achieve.

Playing Without Instructions: The Sculptural Freedom of Shek Lei

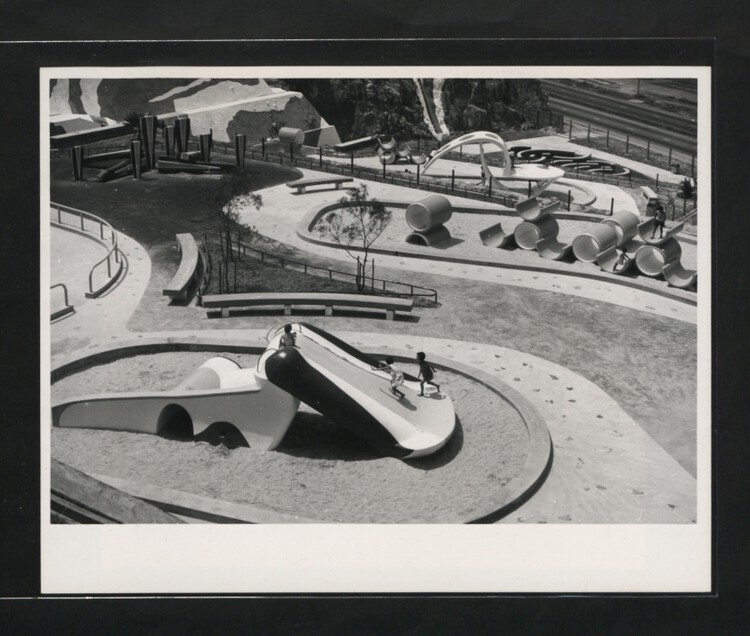

Noguchi's influence found its way to Hong Kong. Shek Lei Playground, one of the city's first major public play spaces, opened in 1969 and incorporated many of the design philosophies present in Noguchi's playscapes. Designed by Paul Selinger, an American artist living in Hong Kong at the time, the playground offered an alternative vision of play—one rooted in imagination, reinterpretation, and user-led exploration.

Rather than relying on prescriptive equipment like slides or swings, Shek Lei Playground encouraged children to invent their own ways of engaging with its sculptural forms and land-based structures. Deliberately ambiguous and open-ended, the playground offered a spatial experience that was as provocative as it was liberating. In stark contrast to today's hyper-specific play equipment, it treated play as an act of creativity—one rooted in exploration, risk-taking, and self-discovery.

Fan Lok Yi, author of The Abstract Playscapes of Hong Kong, notes that many European and American designers from the 1930s to the 1970s created abstract sculptures that doubled as play structures. These forms, which did not dictate a specific mode of play, were seen as more effective in stimulating children's imagination and creativity than traditional playground equipment. As a former British colony, Hong Kong's early playgrounds were shaped by these design influences—evident in the sculptural, non-prescriptive elements that characterized spaces like Shek Lei.

"...... local designers have still tried to create exciting playscapes using simpler phyislca forms, sometimes integrated with imported facilities." - Fan Lok Yi

Standardized Safety: The Decline of Imaginative Public Spaces

However, this very ambiguity also posed challenges. While the open-endedness invited creative freedom, it also allowed for unintended and potentially hazardous forms of use. These sculptural play environments—often integrated with the landscape—were not designed with contemporary safety standards in mind. The absence of fall protection, soft surfacing, or clear usage protocols led to rising concerns over safety. In both Hong Kong and the United States, a growing number of injury-related lawsuits internationally influenced the gradual shift of public policy and industry standards.

As a result, municipalities and playground manufacturers increasingly prioritized legal protection over experiential richness. In an effort to minimize liability, city departments and design agencies gravitated toward standardized solutions. This shift gave rise to the modular, pre-approved playground: safe, replicable, and entirely devoid of ambiguity. Additionally, the preference for non–site-specific play equipment—requiring minimal sitework, landscaping, or customization—was likely more cost-effective for local governments. Beyond reducing upfront construction costs, this approach also allowed for greater flexibility in land use, enabling the playground to be easily removed or repurposed in accordance with shifting urban policies.

This risk-averse shift created a generation of homogenous, overly prescriptive play spaces that, in focusing child's safety and protecting institutions, inadvertently suppressed the creativity and imagination of children. What was once an invitation to explore became a closed system of predictable interaction—removing the very qualities that made play meaningful in the first place.

Reclaiming Play: How Hong Kong Is Rediscovering the Power of Ambiguity

Fortunately, there has been a renewed appreciation for ambiguous play sculptures and spatial exploration in Hong Kong, thanks in part to initiatives led by the Playright Children's Play Association (Playright), an NGO founded in 1987. In collaboration with the Central and Western District Office, Playright developed WE Park along Fung Mat Road Waterfront—a project that reintroduces the spirit of Shek Lei Playground's open-ended, non-prescriptive play into the contemporary urban landscape. Designed to promote creativity and self-discovery, WE Park offers an alternative to formulaic playgrounds, encouraging both children and adults to invent their own ways of engaging with the space.

Nicknamed Tunneling Park by the community, the park features a series of concrete tubes in varying diameters and sectional forms. These simple yet provocative geometries inspire diverse uses, from imaginative hide-and-seek to physical exercises. The park has become a popular destination not just for children, but also for joggers, families, and passersby along the harborfront—demonstrating how open-ended play can foster cross-generational engagement. Echoing Isamu Noguchi's belief in abstract forms as a primer for movement and imagination, WE Park celebrates his philosophy by creating spaces that challenge the body's range of motion while nurturing a deeper awareness of environment and scale.

Noguchi's influence on Hong Kong's urban playscapes has, indeed, come full circle. Beyond inspiring WE Park, his work has also been integrated into the rooftop of M+, the city's flagship museum designed by Herzog & de Meuron. M+ Playscape, opened in 2022, features several elements drawn from Noguchi's public play sculptures, including benches adapted from California Scenario (1980–1982, Costa Mesa, USA), multiple configurations of Octetra, a Play Pyramid from Kodomo no kuni (1965–1966, Yokohama, Japan), and a Play Mound inspired by Piedmont Park's Playscapes (1975–1976, Atlanta, USA). According to the museum, these installations aim to inspire experiential experimentation with our bodies, our minds, and our environments—reaffirming play not as a childish diversion, but as a vital form of learning, spatial awareness, and civic engagement.

This article is part of the ArchDaily Topics: Shaping Spaces for Children, proudly presented by KOMPAN.

At KOMPAN, we believe that shaping spaces for children is a shared responsibility with lasting impact. By sponsoring this topic, we champion child-centered design rooted in research, play, and participation—creating inclusive, inspiring environments that support physical activity, well-being, and imagination, and help every child thrive in a changing world.

Every month we explore a topic in-depth through articles, interviews, news, and architecture projects. We invite you to learn more about our ArchDaily Topics. And, as always, at ArchDaily we welcome the contributions of our readers; if you want to submit an article or project, contact us.