I love putting together lists of original manifesto-like statements by architects perpetually searching for breaking new ground. They provoke us to imagine possibilities we haven't dared to consider before. Questioning conventions should be a critic's primary objective to engage in a conversation with a creative. Otherwise, what is there to discuss, really? That's why speaking with Elizabeth Diller about her studio's work and intentions is like a breath of fresh air, especially nowadays when so many architects are happy to align themselves in pursuing what's expected. In one of our previous conversations, Diller put it bluntly: "We don't take professional boundaries seriously. Every time we are handed a program, we tear it apart and continuously ask new questions. Nothing is fixed." This time, we spoke about Diller Scofidio + Renfro's new monograph, "Architecture, Not Architecture." The book, a project in itself, aims to rethink the very limits of architecture. It reinvents what a book can be in the process. During our 1-1/2-hour discussion over Zoom, which I prefer for its frontal dual recording, she said eagerly, "We were always critiquing; we were always throwing grenades at things."

In our conversation, we touched on many topics. Diller described the new book's structure, why the studio resisted producing it for so long, selecting the content, its design, and how the partners envisioned it to be unlike any other monograph. She said, "If we were going to do it, we would do it on our terms." So, the architects turned their book—two conjoined books in one and an engaging insight into over 100 projects presented across almost 800 pages with 2,000 images—into a project in itself. The book's title, "Architecture, Not Architecture," is a binary play that characterizes many of DS+R's works. In the case of this project, the binary is false and purposely provocative since the architects believe that the projects included in the "Not Architecture" half—art installations, exhibitions, performances, scenography, artifacts, gadgets, and other site-specific and thought-provoking experiments—are all architecture, of course!

The two volumes are literally inseparable. They can be examined individually, but you can't separate the two; one supports the other—conceptually, aesthetically, and physically. Interaction, cross-reference, and identifying commonalities is an intrinsic part of it. Going through this multi-track journey, I realized there were no initial sketches or doodles to help walk us through the design process. Diller explained that the intention was elsewhere. Quick diagrams describe projects' design strategies sufficiently. The point was to explain the work simply by presenting it and interrupting its flow through the insertion of relevant and stimulating dialogues, letting the readers discover all sorts of ideas and inquiries either for the first time or unnoticed earlier.

Related Article

"Making Problems is More Fun; Solving Problems is Too Easy": Liz Diller and Ricardo Scofidio of Diller Scofidio + RenfroCuriously, the book engages in a dialogue with the studio's own work, most apparently with an early Eyebeam Museum competition-winning project. This unfortunately unrealized project is defined by a ribbon that separates two flows of intertwining spaces—those where art is produced and those where it is put on display. This clash of programs provokes the interaction between things and ideas typically held at bay. The book does exactly that—instead of telling us what architecture is, it forces us to think of its potential.

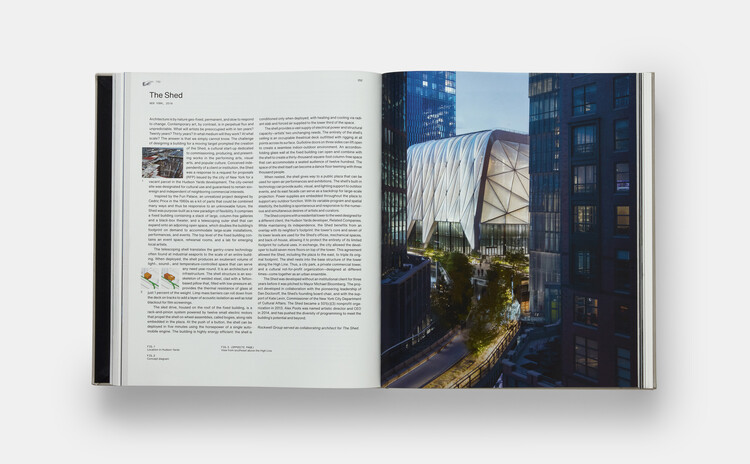

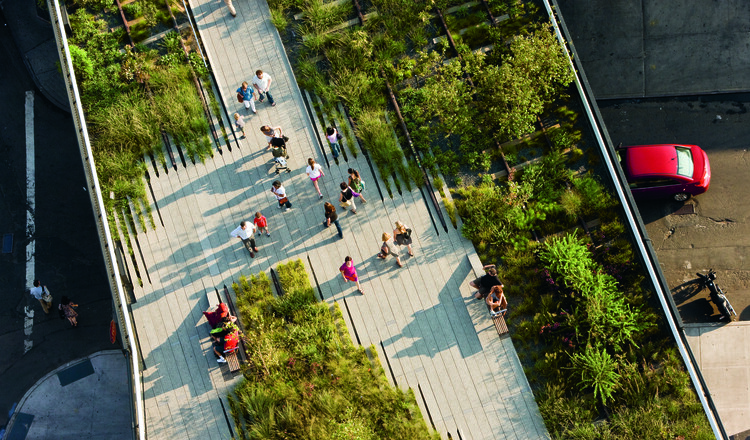

"We were interested in rethinking conventions," Diller asserted. At one point, I offered to go over one of my long lists of the architects' interests and obsessions: artificial nature, boredom, consumerism, crime, discomfort, domesticity, exhibitionism, fashion, glass, happiness, robots, surveillance, tourism, visuality, voyeurism, water, weather, etc. These were explained through detailed excurses into several quintessential projects the studio has become identified with: the Blur Building, the High Line, The Shed, Lincon Center, and MoMA. We also spoke about Canal Café, for this year's Venice Architecture Biennale in collaboration with Aaron Betsky. The architects will purify water out of the Venice Canal and turn it into an espresso, the best in Italy. Diller will serve the first cup.

"Anything you learned from the process of making this book?" I asked in conclusion. "It was therapeutic! It was eye-opening to go to the very beginning, 1981. There is no project in this book that I feel embarrassed about. We believe in everything we did before, and it represents us today."

Elizabeth Diller (b.1958, Łódź, Poland) is a partner of Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DS+R), which she co-founded with Ricardo Scofidio in 1981. She earned her Bachelor of Architecture from the Cooper Union School of Architecture in 1979. DS+R's cross-genre work has been distinguished with TIME's "100 Most Influential People" list and the first MacArthur Foundation fellowship awarded in architecture. Diller led the realization of quintessential New York projects—the High Line, The Shed, the Redevelopment of Lincoln Center, and the expansion of MoMA. Other projects include the Blur Building in Switzerland, the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, the Broad Museum in Los Angeles, Zaryadye Park in Moscow, and the Granoff Center for the Creative Arts in Providence. Diller is a Professor of Architectural Design at Princeton University. DS+R's book, "Architecture, Not Architecture," is the studio's first comprehensive monograph.

Vladimir Belogolovsky (b. 1970, Odesa, Ukraine), a New York City curator and critic, has run his Curatorial Project since 2008. He earned his Bachelor of Architecture from the Cooper Union School of Architecture in 1996. Belogolovsky interviewed more than 500 architects and authored 20 books, including Imagine Buildings Floating Like Clouds, China Dialogues, Conversations with Architects, Harry Seidler: LIFEWORK, Soviet Modernism: 1955-1985, and Architectural Guides Chicago and New York. He curated exhibitions in more than 30 countries, including at the Venice Architecture Biennale (2008, 2014, 2025) and Buenos Aires Architecture Biennial (2017, 2019, 2024).